On Thursday 17 March 2021 the most anticipated “airdrop” in recent NFT history happened.

150 million tokens of ApeCoin (“$APE”) were claimable by Bored Ape and Mutant Ape NFT holders. Today these tokens are valued at $1.95 billion.

Each Bored Ape NFT holder was able to claim 10,094 tokens; each Mutant Ape NFT holder was able to claim 2,042 tokens. The total supply of $APE is fixed at 1,000,000,000.

In this paper I will explain how on earth $APE - which did not exist before Thursday 17 March 2021 - instantly became worth real money to the extent that at the time of writing this paper:

1 $APE = $13

A Bored Ape NFT holder has essentially been given $131,222 (10,094 x $APE price)

A Mutant Ape NFT holder has essentially been given $26,546 (2,042 x $APE price)

$APE has a market cap of $3,477,500,000 (Circulating $APE supply x $APE price)

(Circulating $APE supply = 267,500,000 - comprised of 150,000,000 tokens to BAYC/MAYC holders + 117,500,000 tokens to DAO treasury)

$APE has a fully diluted market cap of $13,000,000,000 (Total $APE supply x $APE price)

$APE allocation: details of $APE allocation and lockups

$APE allocation for NFT holders: how $APE is distributed between NFT holders

This is not a paper purely focused on $APE, but on the “immaculate conception” of token value from what appears to be thin air.

I hope it helps to explain from where the “value” is “made” in newly-created tokens.

Liquidity pools

For a token to have value there needs to be a liquidity pool.

Liquidity pools (LPs) are pools of tokens which are locked in a smart contract. They facilitate trading on decentralised exchanges like Uniswap or Sushi. This means that people can buy and sell them freely, which allows market forces to take effect so that the token can arrive at a ‘market value’.

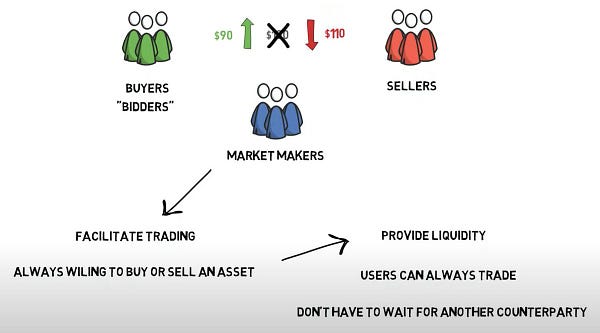

In ‘normal markets’ with which you may be more familiar, a traditional order book model is used to facilitate trading: buyers want to buy for low prices; sellers want to sell for high prices; and market makers exist in the middle to always buy or sell an asset (providing liquidity) so that users don’t literally have to wait for someone else to take the other side of the trade.

This doesn’t quite work in decentralised finance.

It would require market makers to constantly change their prices which would require a huge number of orders and cancelations - a process which would be expensive and unsustainable on Ethereum.

So liquidity pools instead work by holding two tokens and creating a market for that pair of tokens.

What is the incentive to provide liquidity?

When you provide liquidity you are given LP tokens in proportion to how much liquidity provided.

When a trade is facilitated, a fee is distributed to you as a LP token holder.

As such, you are rewarded for providing liquidity by a cut of the transactions taking place.

How does the liquidity pool actually work?

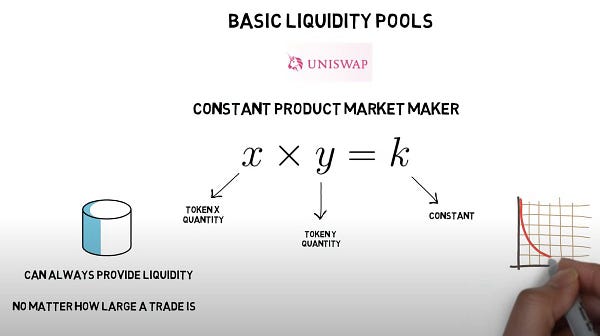

The product of the supply of the two tokens always remains the same.

An algorithm increases the price of the token as the demand increases so a pool can always provide liquidity no matter how large a trade is.

The price of a token changes depending on the size of the trades in relation to the size of the pool.

For example, if you buy $APE with ETH, the ETH supply increases and the $APE supply decreases, so the ETH price decreases and the $APE price increases.

How is the initial token price decided at the start of the liquidity pool?

The initial token price is decided by the ratio at which tokens are supplied to the pool by the first liquidity provider.

Let’s use $APE as an example.

In order to establish the $APE liquidity pool two assets are required: $APE + one other.

In most cases the other asset will be WETH (Wrapped ETH) - but I will use USD figures since we usually quote token values in USD.

$APE opened at a price of approximately $7.40. (It might have been higher but let’s just go with the chart number for now.)

It’s a bit tricky to go back to find out precisely in what proportion liquidity was provided to the pool, but let’s come up with some numbers to understand how it could have worked at least in principal.

In order to arrive at a valuation for 1 $APE, you would need to divide the amount $APE provided to the liquidity pool by the dollar value of the WETH you provide.

So how could 1 $APE arrive at a value of $7.40?

740,000 $APE + 100,000 USD (in WETH) in the liquidity pool

=

740,000 / 100,000 = 7.4

Closing thoughts

It is very worth understanding these mechanics before rushing into creating tokens, buying tokens or providing liquidity.

There are other important factors to consider which are outside the scope of this paper - impermanent loss, liquidity pool hacks, and the general structuring of incentives.

I hope this was a helpful introduction to liquidity pools and the “immaculate conception” of token value.

Have a great day,

B

Please do leave me any questions or thoughts here - I respond to every one!

And if you thought this was interesting, please consider subscribing to this Substack here and following me @BCheque1 on Twitter for more on NFTs and Web 3.0.

Disclaimer: The content covered in this newsletter is not to be considered as investment advice. It is for informational and educational purposes only.

I hold some of the NFTs mentioned in these newsletters.